Everybody

Adaptation History

Unsurprisingly, Everybody wasn’t born from thin air, but neither was the work from which it was most closely adapted, the 15th-century Everyman. In actuality, the heart of the text can be traced all the way back to prehistory, namely to early Indian Buddhism.

Buddhists, who seek transcendence from the single self and the eventual attainment of nirvana (which the Western world might call enlightenment), largely follow the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, the original Buddha, who lived upwards of 2,400 years ago. These lessons, like any religion, take the form of fables and stories from the lives of their founders. However, as our production emphasizes, nothing in our world is exempt from the influence of ourselves and each other, and thus the fables of the Buddha’s life have been constantly retold, refashioned, and altered; of the many versions of the Buddhist legend, we can now identify the tale of saint Josaphat as a Christian retelling of the Buddha’s own life and teachings. The common story of Josaphat, similar to its Buddhist origin, warns against the “false friends” of wealth and earthly connections, and exalts good deeds (and, of course, the Christian faith) above all else. This is the form the Buddhist parable took when it eventually reached Western Europe, and more specifically, the Dutch Low Country, where it inspired Peter van Diest’s Elckerlijc in the 15th-century. This text was part of a growing tradition of Dutch scholarship in the dramatic arts and may have stood as an early attempt at public relations.

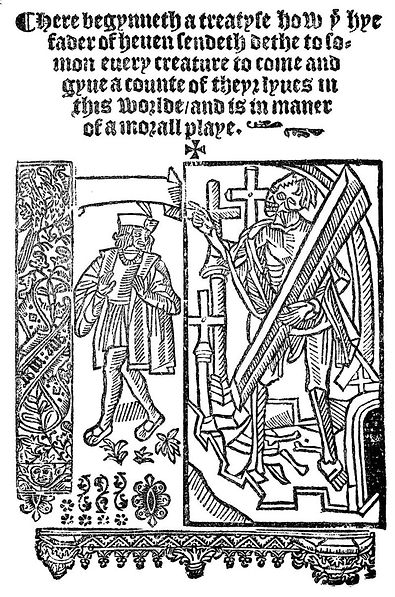

Currently, it’s thought Elckerlijc served as the most direct source material for the anonymous English author/s of Everyman (otherwise known as The somonynge of every man), though the latter would greatly surpass the former in terms of popularity, even coining the phrase “morality play,” a genre defined by the instilling of Christian values through allegory. It is from this English play that Branden Jacobs-Jenkins forged Everybody, which premiered Off-Broadway in 2017. Though it departs notably in certain areas, this adaptation is remarkably similar to Everyman, with certain lines and jokes being almost direct translations from Middle English. Jacobs-Jenkins references Everyman, Elckerlijc, and even the original Buddhist teachings in Everybody, making clear that he, like our production team, is keenly aware of the significance of this story’s travels across time, space, lives, and cultures.

Works Consulted

Davidson, Clifford. “Everyman and Its Dutch Original, ELCKERLIJC: Introduction.” Everyman and Its Dutch Original, Elckerlijc: Introduction | Robbins Library Digital Projects, Robbins Library Digital Projects, 2007, https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/davidson-everyman-introduction.

“Everyman, a Morality Play.” British Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/everyman-a-morality-play.

Waite, Gary K. Reformers on Stage: Popular Drama and Religious Propaganda in the Low Countries of Charles V: 1515-1556. University of Toronto Press, 2000.

Wilson, J. A. “The Life of the Saint and the Animal: Asian Religious Influence in the Medieval Christian West”. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, vol. 3, no. 2, July 2009, pp. 169-94, doi:10.1558/jsrnc.v3i2.169.